Enjoy Lucerne Fountain Water

The City of Lucerne has provided us with fresh drinking water for over 600 years. Thanks to over 200 fountains with drinking water of the highest quality, we never have to do without, even when on the go. That is why we want to encourage you to use these fountains as your go-to water source when you are out and about in Lucerne. Use our Guide to find your way to the nearest fountain and enjoy some of the best water in the world, free of charge! In addition, click here to receive an environmentally friendly stainless steel bottle from lucernewater.ch. Keep scrolling to learn more about the rich history behind the water supply sector in Lucerne.

Did you know that the old well network has provided the overwhelming majority of the city’s fountains with spring water from Kriens since the Middle Ages? What’s more, this well network functions independently of the remaining pipeline network, requires no electricity and can therefore provide the city with top quality drinking water even in cases of emergency.

The Lucerne Water Bottle can be filled free of charge at numerous fountains.

© lucernewater.ch | Franca Pedrazzetti

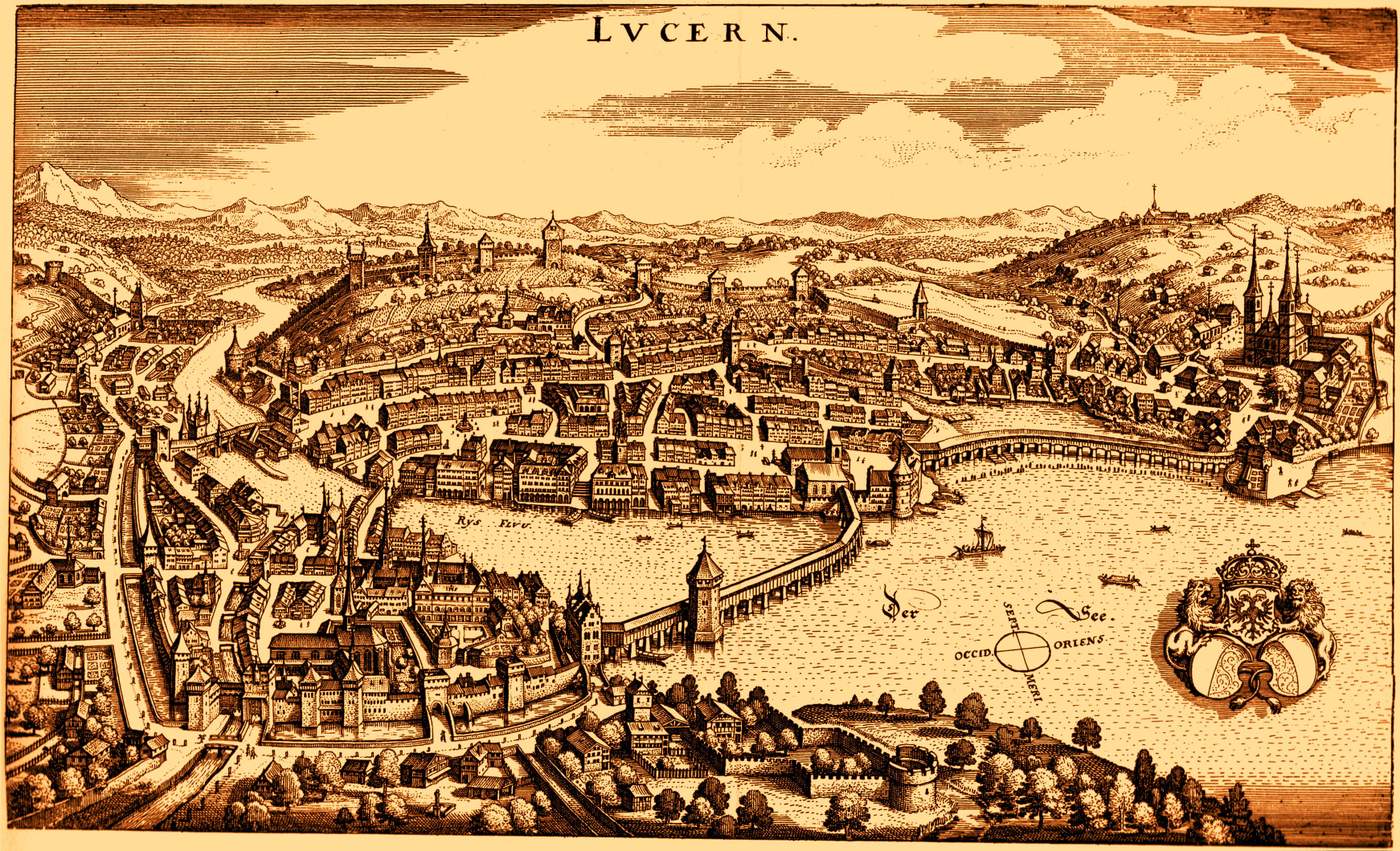

Since the city’s foundation in the 12th century, fountains have shaped the history of water provision in Lucerne. Let's take a look at one example. More information on individual fountains and the quickest route to them can be found in our Guide.

Fritschi Fountain

The legend of Bruder Fritschi probably dates back to the victory over the Austrian Supremacy during the Old Zurich War. With the support of guilds from Lucerne they were defeated at the Battle of Ragaz on 6th March 1446 (Fridolinstag). The grave of lansquenet Fritschi is said to be located beneath the fountain on Kapellplatz. Today, the Zunft zu Safran commemorates the fountain every carnival by circling it three times and throwing oranges to the surrounding people.

Picture above: Fritschi Fountain.

© lucernewater.ch

Lucerne drinking water is clean and rich in important minerals. But how did it come to be that the drinking water of Lucerne is among the best in the world? In order to answer this question, let’s look behind the scenes of our water supply sector – exhibiting decades of excellent, yet hardly visible work.

Water Supplier in the Public Interest

The private holding company ewl energy water lucerne is under contract to the City of Lucerne and is responsible for the reliable supply of water. The public-private scheme has two particular advantages: for one, maintenance and development is clearly regimented and guarantees sound pipeline networks all the way to the home. Secondly, a balance is struck between the public interest in regulated water prices and the economic efficiency of the company.

Picture above: Waterworks.

© ewl

Water Supply Quality and Safety

ewl owns, services and builds catchments, reservoirs and water pipelines and is obliged to provide first class water quality to every household connection. Its sophisticated system guarantees complete reliability of supply even in the case of a complete failure of any of the water sources (spring water, ground water or lake water). In case of emergency the highest daily consumption from the past 10 years acts as the benchmark for the volume of water.

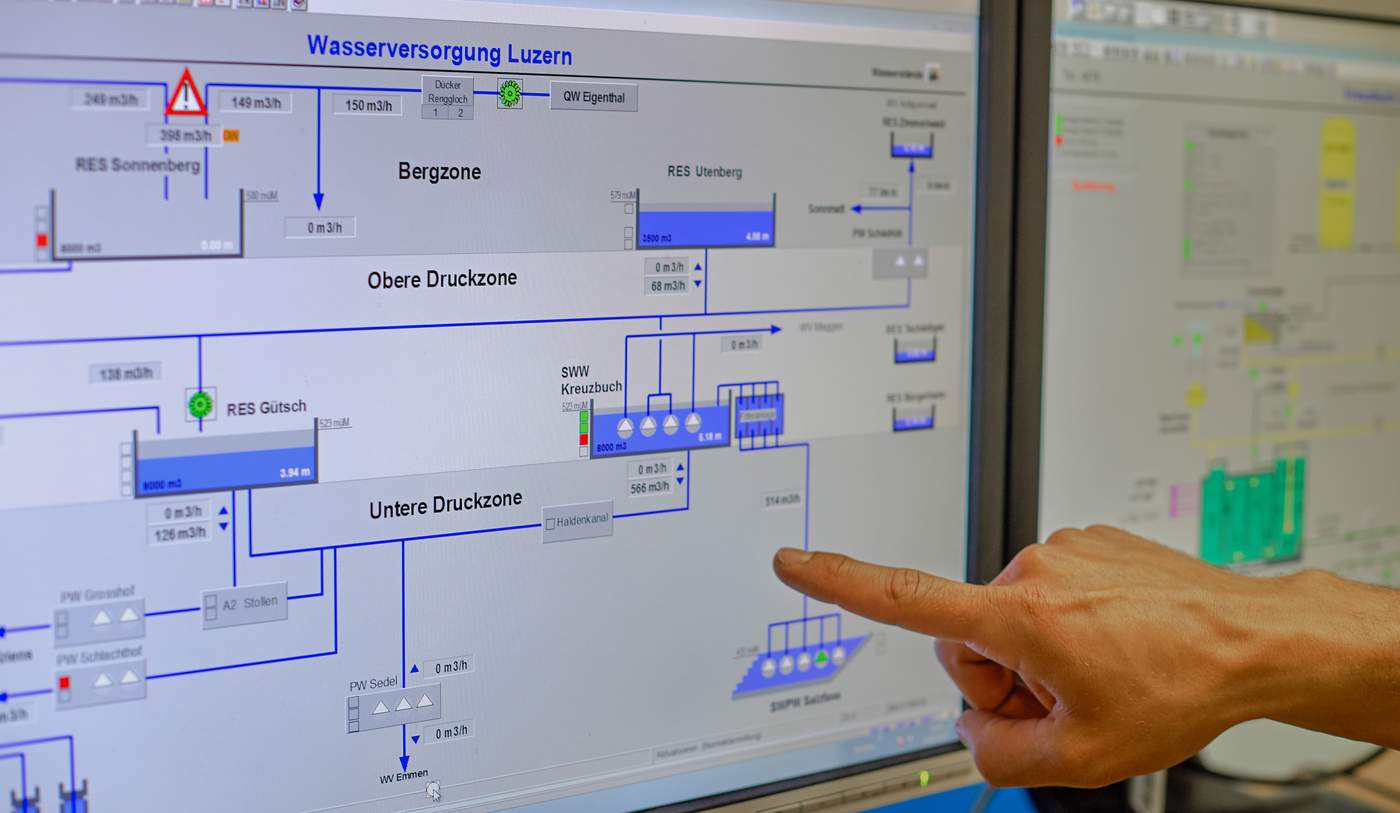

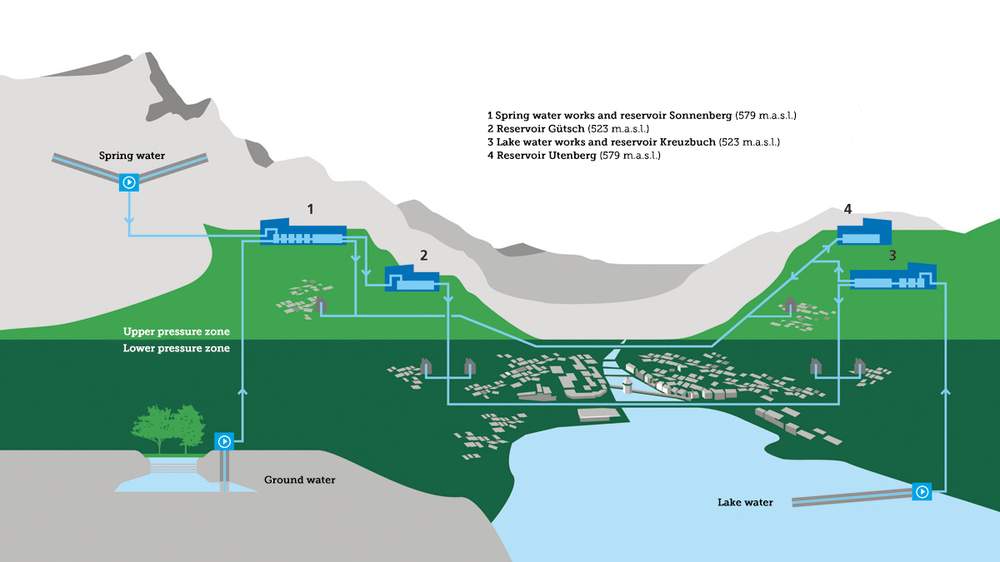

The Supply System

Lucerne water is distributed across six reservoirs and through a complex pipeline network to the city’s households and fountains. The system is comprised of two different pressure networks and the old well network.

Picture above: Valley of the small Emme.

© lucernewater.ch | Franca Pedrazzetti

The water supply network of the City of Lucerne. The reservoirs are built symmetrical to balance the pressure. The well network

is separated from the household system.

© ewl

Mains water is distributed across two pressure networks into the households of Lucerne. The high pressure zone obtains water from the Sonnenberg, Littau and Utenberg reservoirs. The low pressure zone obtains water from the Kreuzberg, Zimmeregg and Gütsch reservoirs. This distribution adapts the pipeline pressure necessary to reach the higher neighbourhoods of Lucerne and is, thanks to the efficient use of gravity, very environmentally friendly. Finally, the old well network obtains water from the Kriens source at the foot of Mount Pilatus and provides it to most of the fountains in the old as well as new city. Around 11 billion litres of water flow through this network each year.

The supply network of the city of Lucerne is fed by three different water sources: lake water, spring water and ground water. In order to better understand why Lucerne drinking water is of such high quality, we must look more carefully at their origins.

Lake Water

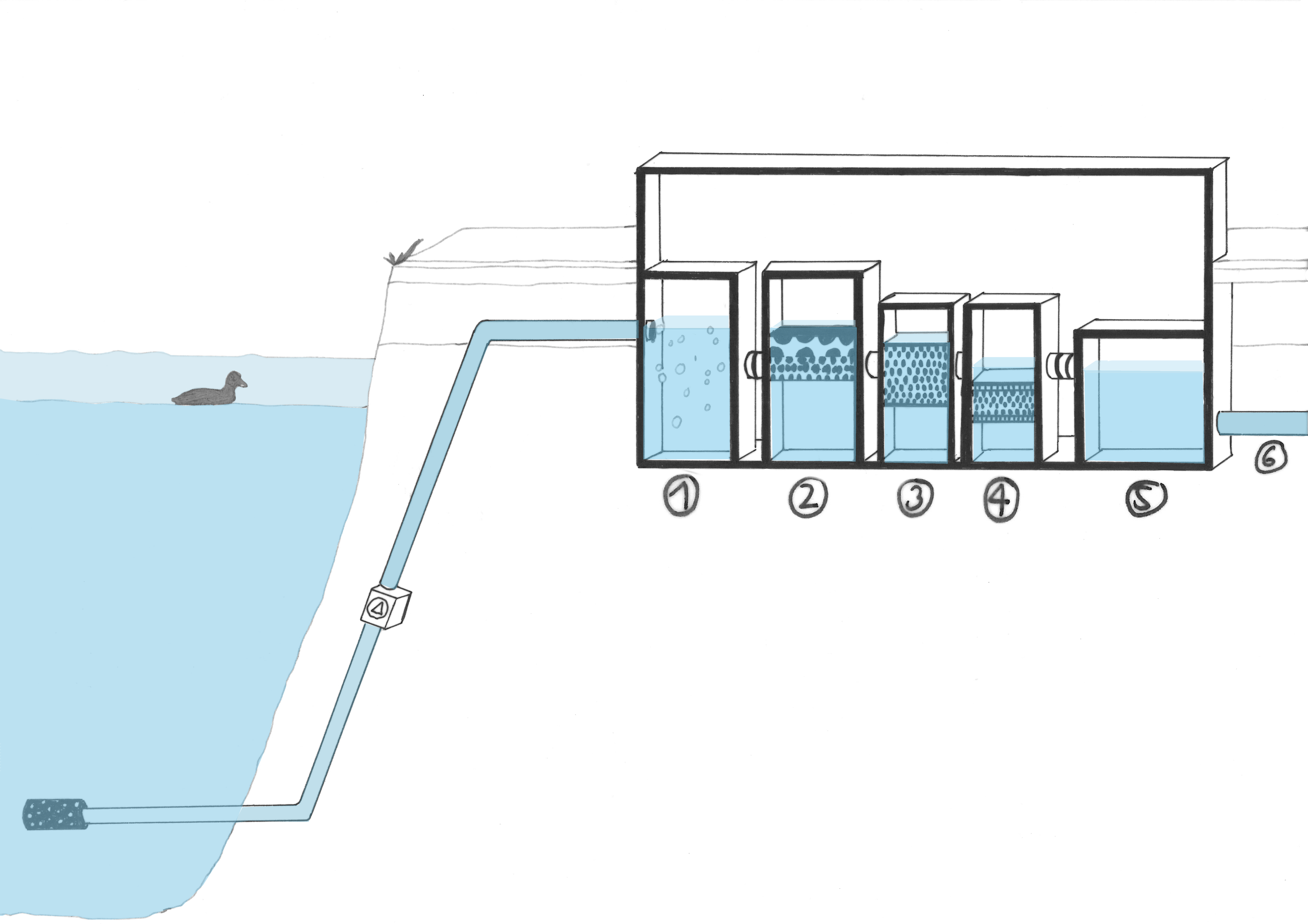

Approximately 50% of Lucerne's drinking water comes from the Lake Lucerne. This water has been purified and distributed by the Kreuzbuch water works since 1966. Water from various tributaries is stored in the lake basin for a long time and is subjected to the influences of goings-on in the city and its surroundings. Thanks to strict water protection guidelines, the Lake Lucerne is very clean and already of drinking water quality even without treatment. Nonetheless, equally strict guidelines for tap water demand further treatment in order to eliminate even the smallest of residues.

Picture above: Lake Lucerne.

© Lucerne Tourism

From the lake to the home:

1: Ozonation, 2: Quartz Sand Filter, 3: Activated Carbon Filter, 4: Chlorination, 5: Reservoir, 6: Pipeline

Ozonation preventively kills germs and bacteria, quartz sand filters larger particles, activated carbon breaks down biologically active substances and chlorine dioxide prevents microbial growth in the network. From the Kreuzbuch reservoir the lake water flows into Lucerne’s households. These processes are relatively energy intensive, however the costly treatment is made up for by the sheer volume of the lake, making it an attractive water source.

Spring Water

For over 600 years spring water from the Pilatus has flowed into the city. A distinction is made between the old Kriens source and the newer Eigenthal source, which has provided the city with water since 1875. The new spring water works at Sonnenberg in Kriens is one of the most modern supply works worldwide. The share of spring water will be increased up to 40 to 50% within the next years.

Picture above: Mount Pilatus.

© Lucerne Tourism

The spring water in Eigenthal is practically untouched by any influences of civilisation and has therefore no micro-impurities.

© Lucerne Tourism

Spring water goes through a variety of natural cleaning processes. The water flows over gravel and rocks in the mountains and trickles slowly through various layers of soil into the underground. As a result, the water is cleaned and absorbs important minerals such as magnesium or calcium carbonate. Shortly before exiting the soil, the water is collected by drainage pipes and directed into the spring water works.

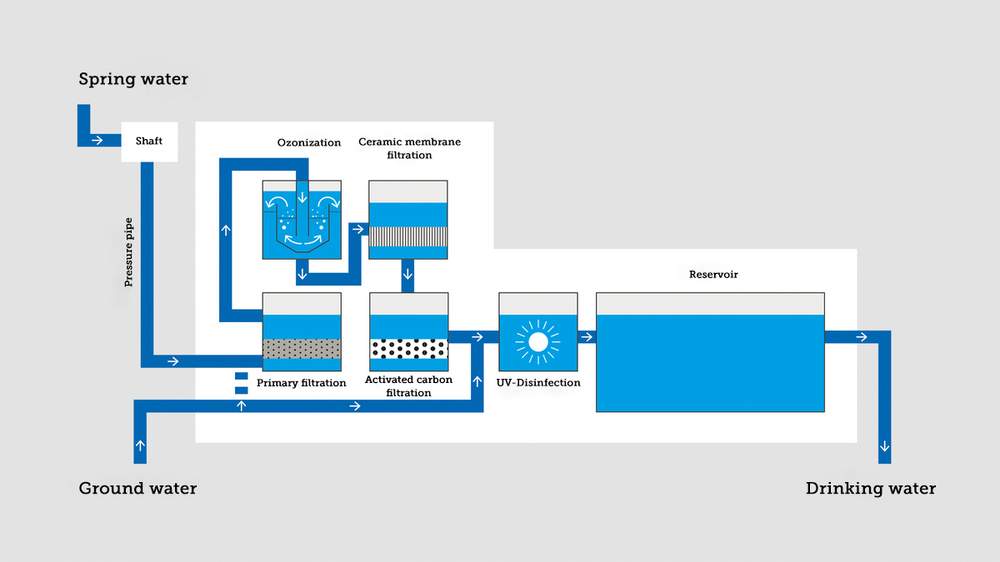

From the Spring to the home:

The ceramic membrane filter is one of the most modern filtration systems worldwide. It treats the water without any chemicals.

Spring water shows no micro-impurities caused by civilisation. In addition, the differences in altitude cause a high pressure, lowering the amount of electricity needed for the treatment and distribution of water. This makes spring water the most ecological and inexpensive variant of water collection. Investing in spring water therefore directly benefits the environment and ultimately us. The new spring waterworks located on Sonnenberg with one of the most modern filtration systems worldwide will enable even more spring water to flow into households in Lucerne in the future.

Ground Water

The remaining drinking water is ground water from the valley of the small Emme. Water from this source has been tapped by the city since 1907. Ground water trickles deep into the layers of soil and consequently absorbs many minerals. This has a positive impact on the intensity of flavour. A shaft with small columns is created for the collection of ground water. Water flows through it and is subsequently pumped into a reservoir.

Picture above: Valley of the small Emme.

© lucernewater.ch | Franca Pedrazzetti

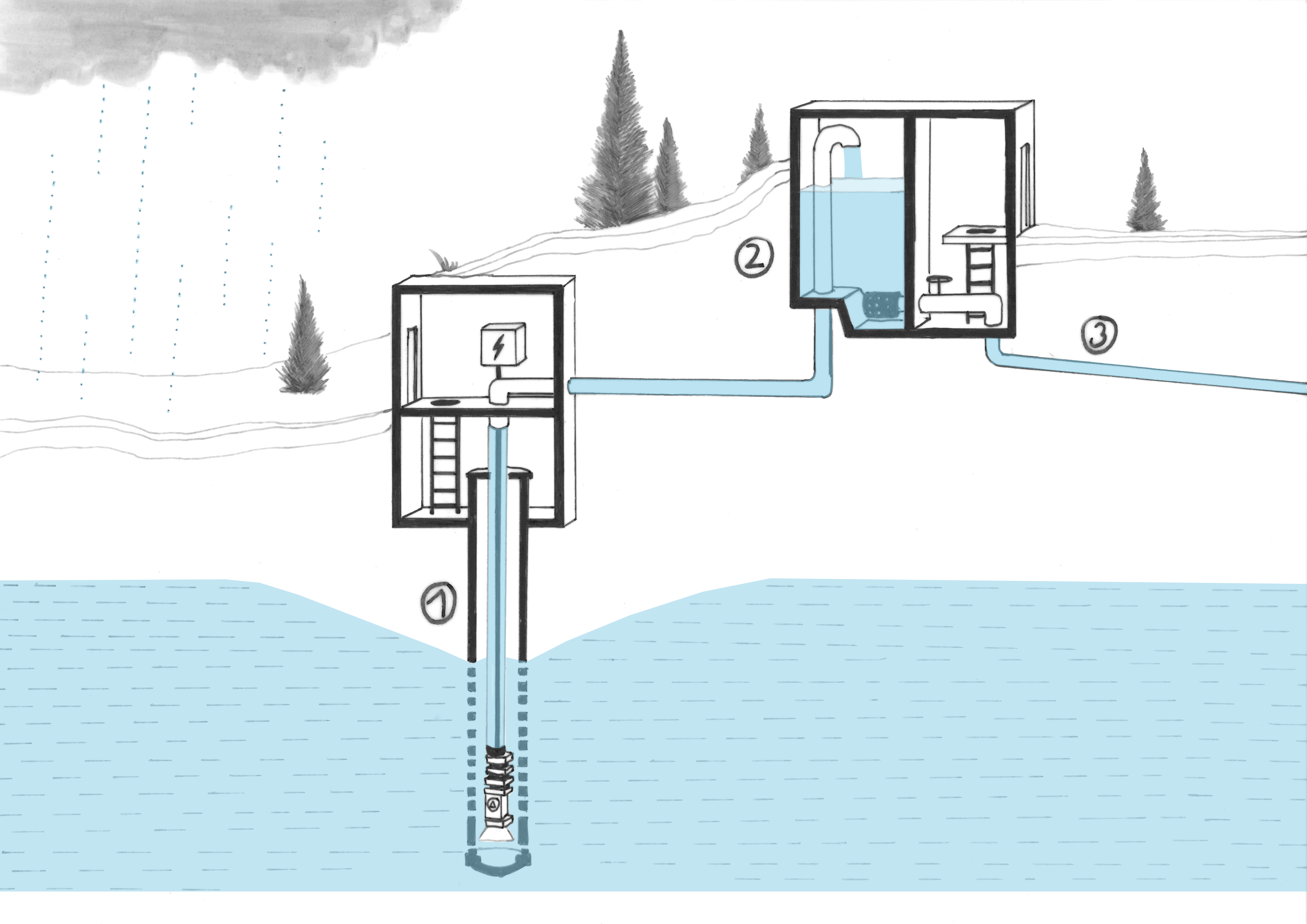

From the ground to the home:

1: Shaft, 2: Reservoir/UV-Disinfection, 3: Pipeline

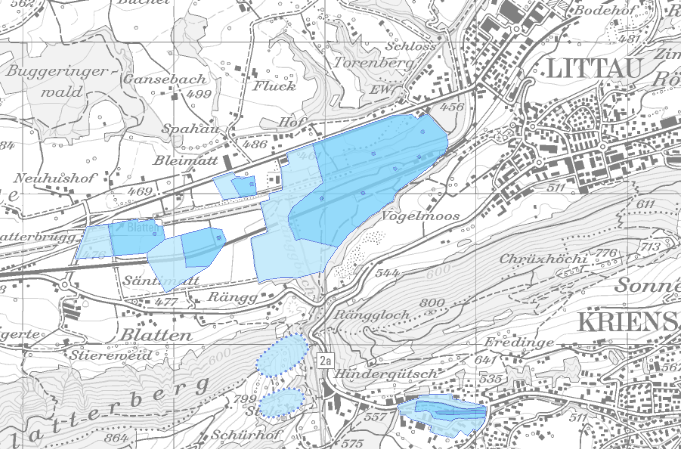

The preventive handling of ground water with ozone is sufficient. This, alongside the already natural cleaning processes taking place while the water seeps through layers of soil, makes the exceptional protection of ground water possible. Any agricultural or industrial businesses and therefore any interference to the water around the ground water works are forbidden.

Protection zones around the ground water works in the valley of the small Emme. The darker, the closer one is to the collection facility, the stricter the protection regulations.

© Geoportal of the canton of Lucerne

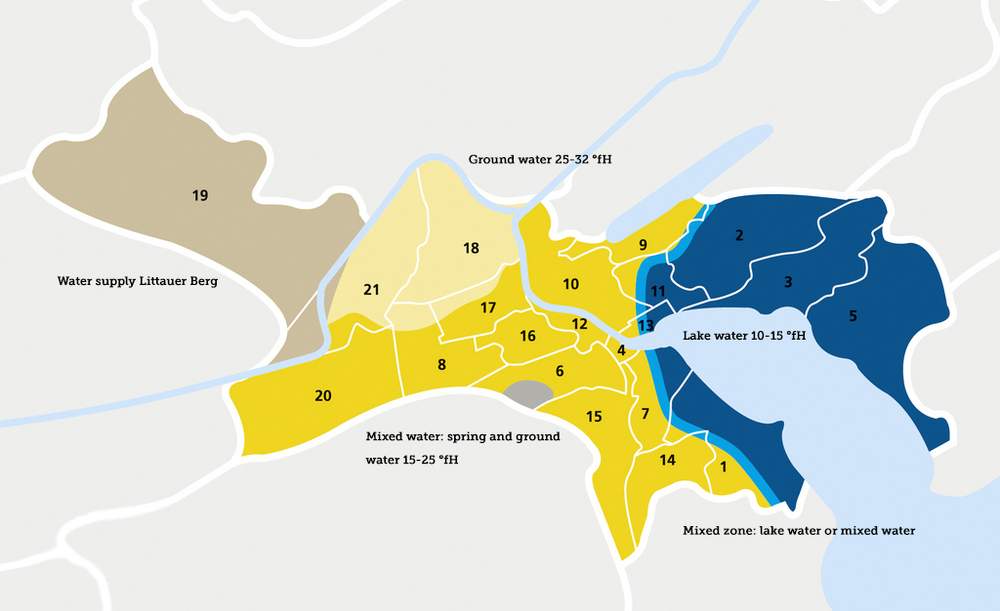

Water Hardness and Distribution

The respective origins of the three water sources determine their water hardness and distribution to each neighbourhood of the city. Let’s take a look at the city plan to see where which water source flows.

Districts of Lucerne and their water hardness.

© ewl

The Benefits of Tap Water

All of the city’s efforts are worth it: Lucerne drinking water is qualitatively excellent, up to 1000x more environmentally friendly than branded bottled water and despite this, it costs next to nothing (1 litre = CHF 0.0015). Fountain water is even free in the entire city! Our water supply today and its benefits are so integrated into everyday life that we barely notice them. This was not always the case. It is therefore worth looking back at history and at a time when water – for better or worse – shaped everyday life.

The history of water provision in the City of Lucerne is closely linked with societal, demographic, medical and structural developments. Health related problems in association with insufficient water provision plagued the city up to the 20th century and caused great suffering, but they also drove the conception of resilient and innovative solutions.

Medieval Wells Trigger Epidemics

The first settlers in the 12th century obtained water from the surface of the Lake Lucerne and the river Reuss. Soon enough, covered wells and cisterns replaced the then insufficiently hygienic surface water. However, these wells were easily contaminated, especially in highly populated areas, and regularly triggered deadly typhoid, cholera and plague epidemics.

Kriens Spring Water Has Been Flowing into the Fountain Network for over 600 years

The history of Lucerne’s fountains traces back to 1417. Their construction was incited either by urban measures for infrastructural development and the improvement of hygiene or simply by complaints from the general public.

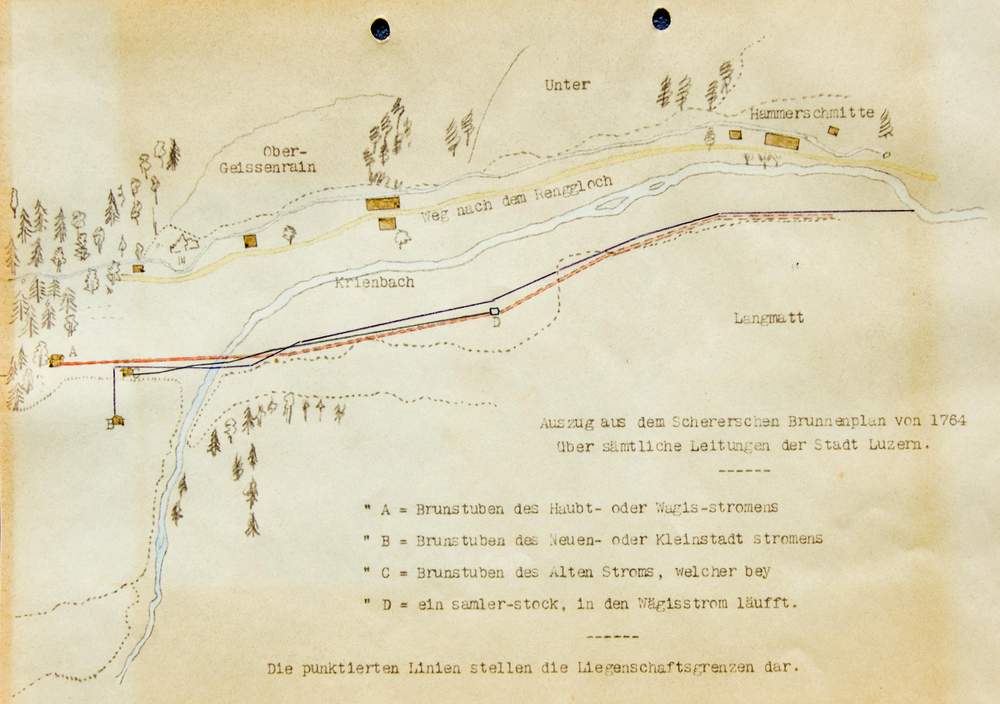

The first tapping of spring water around the Krienbach at the foot of Mount Pilatus with pipelines running into the City of Lucerne.

© City Archive of Lucerne

What is passed down, is the fact that spring water from the foot of Mount Pilatus flows into the city’s fountains since the 15th century.

Privileges for the Upper Class

For a long time, one of these sources was reserved for rich aristocratic families. This points to distribution difficulties as well as interrelated social discrimination. The poorest neighbourhoods of the city struggled with water provision for a long time and many inhabitants had to draw their water from unsafe wells. For hundreds of years the pipeline network was made of oak from the Eichwäldli next to the Allmend.

For several hundred years the material for wooden water pipes was forested and manufactured in ponds.

© Zentralbibliothek Luzern

Despite serious water loss and rotten pipes this system was in use and provided the city with water until 1860. Until well into the 18th century, all newly weds were obliged to purchase and plant a new oak tree.

Fountains as the Most Important Meeting Places of Urban Life

The city’s fountains performed various tasks. They provided people and animals with drinking water and served as wash basins for clothes and boots.

The Weinmarkt Fountain is one of the oldest in the city. It has

provided water and connected residents for over 600 years.

They particularly shaped the social life of the city by serving as a meeting place for the exchange of gossip. It was the modern water supply system at the end of the 19th century that shifted this forum to cafés and restaurants.

Strong Urbanisation Pushes Innovation

The development of the modern water supply system of Lucerne arose mid 1870s out of a precarious emergency situation. In the 19th century Lucerne was rapidly developing into a flourishing city for trade and business. The similarly fast growing population, which had quadrupled in the space of a single generation to 32,000 inhabitants, together with the increasing level of production, was overwhelming the urban water supply. This forced the city to develop radical and innovative solutions.

Picture above: Sonnenberg Reservoir 1874.

© ewl

CHF 1.75 Million for Water Provision

A report from water supply technician Arnold Bürkli from 1872 recorded two decisive aspects for the future: firstly, the public character of the urban water supply was reinforced and secondly, the Eigenthal was identified as the only sensible source area to meet the growing demand.

Arnold Bürkli (here: 1870) with his report laid the foundation for the modern water supply system in Lucerne.

© Ahneninfo.com

As a result of this report, the city council decided upon the then very high sum of 1 million Swiss Francs for the founding of the city’s modern water supply. Eventually, the cost rose to 1.75 million Swiss Francs.

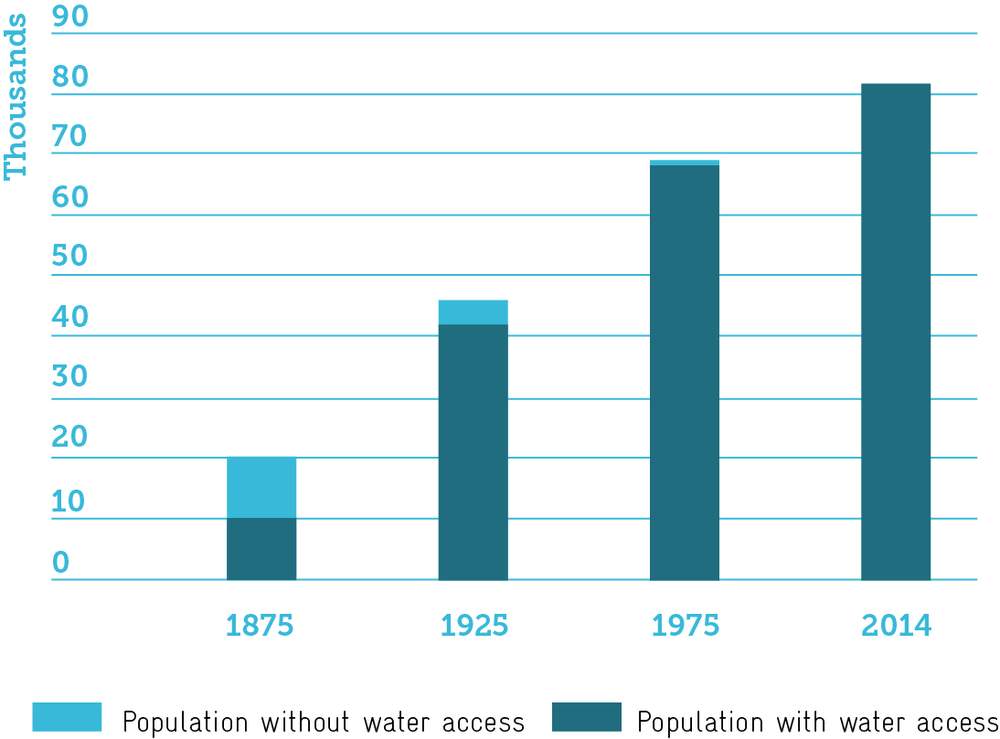

1875: The First Spring Water from Eigenthal Provided Around 50% of the Population with Drinking Water

Already in 1874, the construction of the Sonnenberg Reservoir and 36 km of pipelines began.

Spring tapping of the Bründlen source in Eigenthal; a daring project!

© City Archive of Lucerne

In 1875 Eigenthal spring water flowed into the city’s buildings for the first time. Of the then 16,400 residents around half had safe access to water at home. The rest of of the citizens still had to get their water from partly unsafe wells.

The pipeline network of the City of Lucerne shortly after its completion in 1875. Accurate maps of pipelines and fountains were particularly vital for the local fire department.

© City Archive of Lucerne

Deficits due to Poor Pricing Policy and Conception

Business was bad in the beginning and was operating at a loss, as the 3 Swiss Francs it cost to supply each room with water only covered a third of what the system cost. What was much more critical, however, was the conceptual shortcomings. The water source proved to be less productive and considerably more temperamental than experts had anticipated.This led to distribution difficulties and particularly precarious water shortages in the winter months.

Water Supply for The Rich and The Poor

The city council responded to these troubles with the successive development of the water supply system within the city – especially in the poorer quarters – along with new connections as far as the Entlebuch area. At the turn of the century, around 90% of inhabitants had safe access to water. Nonetheless, water shortages continued to be a problem and the spread of infectious diseases persisted for some time. The first ground waterworks in Emmen came into being in 1907. These structures (wells and ground water works) were continuously expanded in order to keep up with the rising demand of a growing city.

Overcoming a Myth

Interestingly, despite regular water shortages, not a drop from the Lake Lucerne was ever drained. Prejudices against using lake water for consumption purposes and the myth of pure mountain spring water were still all too apparent. It was not until the 1960s that people realised that tapping lake water was truly the only sensible solution quantitatively, qualitatively and economically. As a result, the lake waterworks was built in Würzenbach from 1963 to 1966.

Picture above: Lake Waterworks Kreuzbuch.

© lucernewater.ch | Franca Pedrazzetti

Until the middle of the 20th century impeccable water supply could not be guaranteed to all citizens.

The Birth of ewl

At the same time further reservoirs were established in Gütsch, on the Utenberg and in Kreuzbuch. The network of pipelines was designed to run symmetrically along both sides of the River Reuss in order to achieve equal water distribution to all neighbourhoods, as well as to balance water pressure. Incidentally, the Sonnenberg and Utenberg reservoirs are no higher than 585 metres above sea level (m.a.s.l.), as the city council wishes to avoid overbuilding on these hills. In 2001 the city council transferred the responsibility of operating the water supply system to ewl and thus formed the present organisational structure.

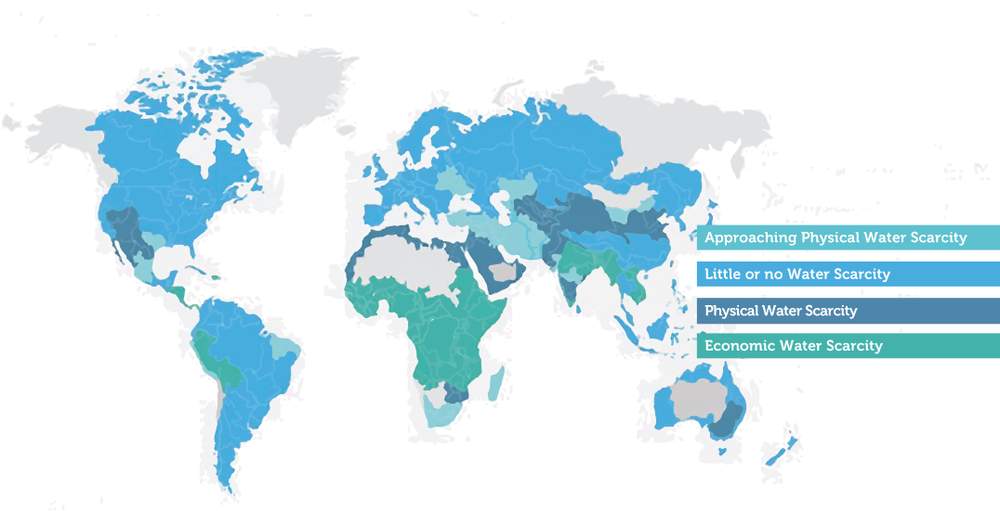

After over 600 years of development in the water supply sector, Lucerne now shines as a wonderful “water city” with taps flowing with first class drinking water. But society and the water supply sector have not enjoyed concurrent development in all parts of the world. Approximately 700 million people worldwide still do not have access to safe drinking water and over 1.8 billion draw water from unclean sources. There is a serious lack of safe water provision for the wider public in Sub-Saharan Africa in particular.

4 out of 10 people in Sub-Saharan Africa lack safe access to clean water. The reason for this is not a lack of physical water, but rather a lack of infrastructure and trained specialists, so called economic water scarcity.

Using the Zambian capital Lusaka as an example, we point out the immense challenges faced by local water suppliers in urban areas, the devastating consequences of insufficient water supply systems and possible approaches towards positive change.

Street Scene in Misisi, Lusaka.

© WATER FOR WATER

Urbanisation as Key Factor

Demands on the water supply sector of the city of Lucerne have never been as high as they were in the late 19th century as a result of strong urbanisation. Since the 1990s Lusaka has also been experiencing strong urbanisation, causing the city to face similar challenges as 19th century Lucerne. Only these challenges have taken on larger, dissimilar dimensions in the Zambian capital.

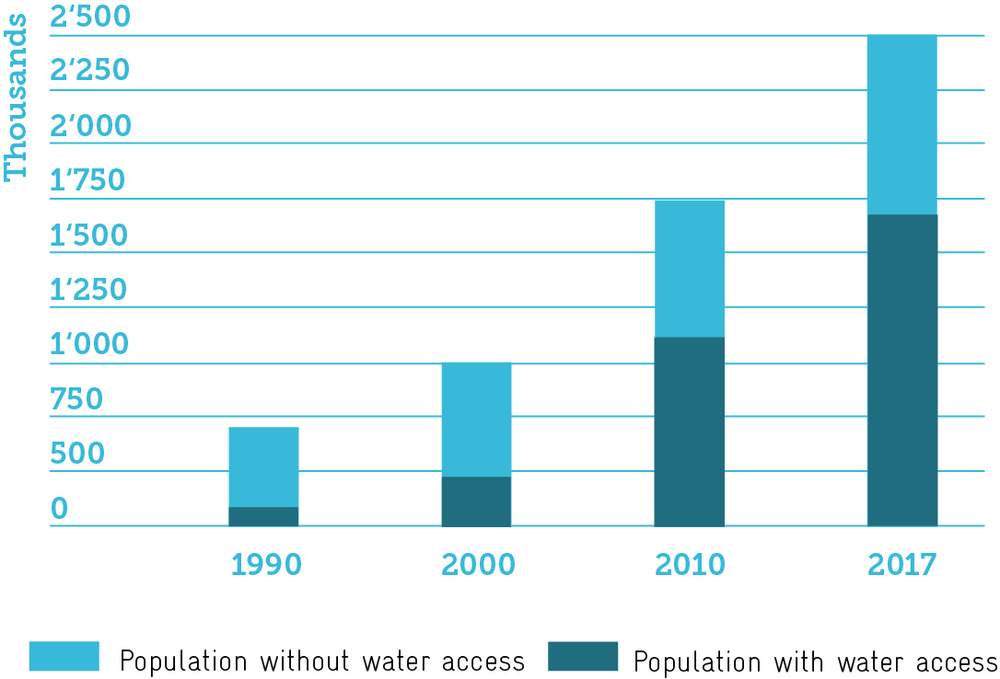

In the last 30 years, more than 1 Mio. people gained access to water. Yet, the local water supplier can't keep up with the rapid population growth.

This exponential growth in a relative small area has huge consequences for the city of Lusaka.

Peri-Urban Areas

Around 65% of the population - more than the ten largest Swiss cities combined - live in structurally disadvantaged, informal urban areas in Zambia's capital Lusaka.

Misisi, one of many structurally disadvantaged peri-urban areas in Lusaka.

© WATER FOR WATER

In these areas the average daily income per capita is less than $1.90, around 60% have no safe access to municipal drinking water and even more live without access to basic sanitation.

Consequences of Inadequate Water and Sanitation Management

The resulting diseases like cholera, typhoid fever, malaria and diarrhoeal diseases, endanger the population of the entire city and do not only bring about great suffering, but also slow down the development of society in many respects for years to come.

Similar to Lucerne, the water supply sector in Lusaka is organised in a public-private scheme. The Lusaka Water Supply and Sewerage Company (LWSC) is owned by the city yet operates according to economic standards.

Luska Water & Sewerage Company

The LWSC is responsible for the development and maintenance of the corresponding infrastructure and for the quality of water.

Planning of new water projects in peri-urban areas of Lusaka.

© WATER FOR WATER

All 11 water suppliers in Zambia are examined yearly by the National Water Supply and Sanitation Council (NWASCO). The NWASCO is furthermore responsible for the regulation of water prices.

Peri-Urban Department

In 2008 the LWSC responded to demographic and urban developments and founded a department devoted to 35 of the fast-growing, densely populated and structurally disadvantaged urban areas. Since then, the construction of supply lines, new boreholes and innovative distribution systems (including water kiosks and household connections financed by a revolving fund) has improved the water supply system little by little.

Supply Sources and Treatment

The water for Lusaka’s water supply network comes principally from two sources: surface water from the nearby Kafue River and ground water. The water from the Kafue River is treated in a multistaged procedure. Ground water is treated with chlorine, which prevents microbial growth and kills typhoid or cholera bacteria.

Picture above: Kafue River.

© WATER FOR WATER

Water Distribution

The treated water is pumped into high tanks and subsequently distributed through gravitational force across a pipeline network into households and water kiosks in the poor neighbourhoods.

Water kiosk in Kanyama, Lusaka.

©WATER FOR WATER

Water kiosks are central water stations connected to a pipeline network, from which residents can obtain clean drinking water at a subsidised price.

The Lack of Infrastructure and Education

Despite good legal and organisational foundations and the water suppliers’ best efforts, the city ofLusaka is far from having comprehensive water supply and waste water disposal systems. Not only are financial means for the necessary development of infrastructure lacking, there are not enough educated personnel in management nor are there enough tradesmen.

The initiator of lucernewater.ch is WATER FOR WATER (WfW). The independent Lucerne-based non-profit organisation promotes the fair and sustainable use of water in Mozambique, Zambia and Switzerland.

Throughout Switzerland, more than 500 businesses and companies are already working with WfW to promote the consumption of tap water and integrate donations for water projects into their everyday operations. In Zambia and Mozambique, WfW is active in structurally disadvantaged peri-urban areas and is committed to ensuring safe access to drinking water, sanitation and hygiene for all.

In all project countries, WfW places a strong focus on education, knowledge transfer and awareness raising.

Development of Water Provision

In collaboration with the city’s water supply sector and the multi-sector organisation Water and Sanitation for the Urban Poor (WSUP), WfW finances and supports drinking water, hygiene and awareness projects in the poorest areas of the city.

Picture above: Laying of a pipe system in John Laing, Lusaka.

© WATER FOR WATER

Support of Self-Containing Systems

One side of this involves the examination of the current situation, going door-to-door for project mobilisation, raising awareness for hygiene and the education of community members; another is the construction of boreholes, pipeline networks, water kiosks and garden connections.

Paying for water at a water kiosk.

©WSUP

As soon as a new supply network is up and running, the population can obtain drinking water at a subsidised price. Those unable to pay receive free water coupons. Thanks to these measures, the system can finance itself and is maintainable. Since 2013, WfW has given over 90,000 people access to safe drinking water in Zambia alone.

Vocational Training

In collaboration with the local trade school Lusaka Vocational Training Centre (LVTC), WfW promotes the education of future plumbers and water operators. This involves helping to finance course fees, as such training positions are expensive and opportunities to study are rare. Furthermore, WfW supports the school in the development of its infrastructure, its teaching materials and the implementation of new technologies.

Picture above: Vocational Training in the LVTC.

© WATER FOR WATER

Connection of Local Stakeholders

Another main concern is the connection of important stakeholders in the water sector with the trade school. A local production company of pipes and accessories as well as the urban water supply sector lead weekly workshops at the school.

Workshop at the local Vocational School LVTC.

© WATER FOR WATER

This is done in order to ensure that the teaching staff are comfortable with the latest technologies and to prepare students specifically for their new career.

Water and Sanitation

The Zambian government has the vision of providing safe drinking water to 100% of the city’s urban areas by 2030. Having said this, safe drinking water is just the beginning. Functional waste water management and adequate basic sanitation are equally influential on the health and quality of life of a society. For this reason, WfW supports partner organisations on location more and more in the planning of future measures in this field.

Since 2018, WfW has also been active in the Mozambican capital Maputo and is strengthening school and community hygiene in structurally disadvantaged urban areas through infrastructure projects. WfW has already implemented comprehensive measures in three primary schools, thereby enabling safe water access and basic sanitation for 6,500 pupils. Learn more about our project work in Mozambique at wfw.ch.